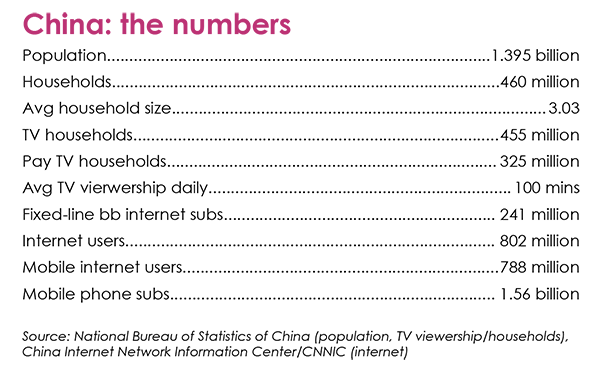

APRIL 2019: While easier access to mainland China remains at the top of international entertainment companies’ lists of things to pray for and eagle eyes continue to be kept on changing regulations, gains are being made outside of thrill rides and blockbuster movies, and the quest for happy endings is ongoing.

Any pretence that China is anything other than tough for entertainment and related sectors – much less foreign operators/programmers – has long been dropped. But lessons have (with some exceptions) been learned, more realistic partnerships are being forged, shifting regulatory sands aren’t the shock they once were, foreign format sales have morphed into various forms of co-development, everyone who’s anyone has a WeChat account, and money is/was being made from licensing deals with streaming platforms as well as with traditional linear services.

And then along came trade war talk, celebrities busted for fiddling their taxes, government investigations into media bosses for a litany of bad things, fears of acquisition cutbacks by domestic streamers struggling to fit video into their bigger ecosystems, and blockbuster drama, Story of Yanxi Palace, which poked the censorship bear in the big way. Or rather, maybe its 15 billion+ streams did, indicating wild popularity and giving rise to fears of undue influence on China’s social fabric. Whatever, it turns out that Yu Zheng’s portrayal of the ancient Emperor’s court is deeply offensive to those in charge of China’s present-day socialist morals.

So that happened and now predictions are that drama coming out of China in 2019 will steer clear of period (or any other) shenanigans from the age of decadence. Meanwhile, in the dawning of the age of thrift, the argument over whether caps on talent fees (and a whole lot of other things that smack of rampant spending) is good or bad depends on which side of the balance sheet you look at. For now, regional producers from outside China, who remain aghast at costs of mainland production, continue their hunt for less costly pathways to Chinese content creation.

Overall, are great things expected from China in 2019? Depends on who you are and where you’ve set your expectation levels.

If you’re BBC Studios right now, things are looking okay, with a shiny new branded space for BBC Earth joining kids destination CBeebies and Top Gear on the Shanghai Media Group’s BesTV IPTV platform from 1 April. The on-demand deal adds titles like Dynasties, Big Cats...

APRIL 2019: While easier access to mainland China remains at the top of international entertainment companies’ lists of things to pray for and eagle eyes continue to be kept on changing regulations, gains are being made outside of thrill rides and blockbuster movies, and the quest for happy endings is ongoing.

Any pretence that China is anything other than tough for entertainment and related sectors – much less foreign operators/programmers – has long been dropped. But lessons have (with some exceptions) been learned, more realistic partnerships are being forged, shifting regulatory sands aren’t the shock they once were, foreign format sales have morphed into various forms of co-development, everyone who’s anyone has a WeChat account, and money is/was being made from licensing deals with streaming platforms as well as with traditional linear services.

And then along came trade war talk, celebrities busted for fiddling their taxes, government investigations into media bosses for a litany of bad things, fears of acquisition cutbacks by domestic streamers struggling to fit video into their bigger ecosystems, and blockbuster drama, Story of Yanxi Palace, which poked the censorship bear in the big way. Or rather, maybe its 15 billion+ streams did, indicating wild popularity and giving rise to fears of undue influence on China’s social fabric. Whatever, it turns out that Yu Zheng’s portrayal of the ancient Emperor’s court is deeply offensive to those in charge of China’s present-day socialist morals.

So that happened and now predictions are that drama coming out of China in 2019 will steer clear of period (or any other) shenanigans from the age of decadence. Meanwhile, in the dawning of the age of thrift, the argument over whether caps on talent fees (and a whole lot of other things that smack of rampant spending) is good or bad depends on which side of the balance sheet you look at. For now, regional producers from outside China, who remain aghast at costs of mainland production, continue their hunt for less costly pathways to Chinese content creation.

Overall, are great things expected from China in 2019? Depends on who you are and where you’ve set your expectation levels.

If you’re BBC Studios right now, things are looking okay, with a shiny new branded space for BBC Earth joining kids destination CBeebies and Top Gear on the Shanghai Media Group’s BesTV IPTV platform from 1 April. The on-demand deal adds titles like Dynasties, Big Cats and Animals with Cameras to BesTV’s line up, and, according to BBC Studios, opens access to more than 46 million BesTV subs across China. We’re not, of course, holding our breath for any public transparency on actual take up/usage, but that’s not unique to BBC or BesTV.

Others in the kids space are making distribution and co-production gains too. Mainland China’s CCTV-14 kids’ channel has added the first two seasons of Tiger Aspect Productions’ Mr Bean The Animated Series to its linear line up across China, Hong Kong and Macau in a 104-episode licensing deal between Endemol Shine and Beijing Yun Hai Xin Yao Cultural Media. In another of a string of kids’ content deals announced for China this year so far, Youku and Hunan TV’s Mango TV bought Digital Light Studio’s pre-school animated property, Sunny Bunnies, from U.K.-based Media I.M. In February, Canada’s Boat Rocker Studios, BBC Children and China’s UYoung said they had partnered on new 2D pre-school animated series, Love Monster, based on the books by British author/illustrator Rachel Bright.

Formats remain a giant talking point (and a bit of a headache for some) in China, as much for their potential as for local rules capping foreign adaptations, mandating domestic IP ownership and arguments over what’s been borrowed without attribution. The most stern position has been taken by international rights agency Frapa (Format Recognition and Protection Association), which, among other things, is pushing for global rights standards and fair exchange between China and the rest of the world. In an open letter towards the end of October 2018, Frapa called for a dialogue “that might lead to open trade and resolution of serious infringement issues facing our community”. Apart from the high-profile legal action between Talpa and Shanghai Canxing Cultural and Broadcast Company in 2016/7 over The Voice of China, Frapa has taken what is possibly the strongest public position on the widely discussed issue of formats/IP protection. “When there is no free exchange of content, and one side does not recognise the inherent value of outside content creation, yet insists on selling and not buying, it can result in misunderstanding, confusion, distrust and bad business practices that harm the entire industry... If a major territory does not respect this business model, we all suffer the consequences,” Frapa said at the time.

Yes, despite the challenges and the alliances that disappear into a black hole after shiny press conferences with lots of people on stage saying nice things to each others’ faces, some real hard-fought-and-won gains are being made across genres, including drama, sci-fi and formats.

The latest of these is a co-developed Chinese version of U.S. scripted format Younger from Endemol Shine Group’s China office. The comedy/drama series, about a 40-year-old woman who passes herself off as 26 so that she can get a job, will be made with production giant, Huace Group.

Also among the latest success stories is Fremantle’s World’s Got Talent, announced finally in February after months and months of stop-start effort to get the show off the ground in China. The 13-part co-development with Hunan TV and Syco Entertainment brings together about 30 acts from the Got Talent franchises around the world. The first-of-its-kind contest is scheduled to air in China in April 2019 as Dian Feng Zhi Lu.

In all, Chinese broadcasters commissioned/acquired at least 31 titles from foreign distributors in 2018, adding everything from local versions of NBCUniversal’s Saturday Night Live talk show to a mixed slate of Japanese scripted adaptations to the local landscape, according to ContentAsia’s Formats Outlook for full year 2018. Endemol Shine, Fremantle and Japan’s Fuji TV have five formats each in China, followed by Japan’s leading commercial broadcaster Nippon TV, which has three. With two each are Singapore’s Mediacorp, Sony Pictures Television and Japan’s TV Asahi.

Japan’s Fuji TV took the Asian scripted drama lead with five of the 16 drama co-developments in China across 2018. But it is Endemol Shine, under China head William Tan, that has given mainland scripted co-developments their biggest potential global footprint.

Endemol Shine surged ahead towards the end of 2018, with a co-development of sci-fi drama series Humans China, which involved extended scripts developed by Chinese and U.K. writers, and a deal for a local adaptation of crime drama Broadchurch. Humans China, filmed in Shanghai, is a partnership with Huace Film & TV’s production subsidiary, Croton Media. Starring Ray Ma and Stephy Qi, the drama is set in 2035, when must-have gadgets are human-like robotic servants and artificial intelligence has infiltrated every aspect of life to dramatic and sometimes sinister effect. The Mandarin-language sci-fi series, based on the eight-episode U.K. version, is the first adaptation of the story in Asia.

Endemol Shine China managing director, William Tan, speaks about new and different types of collaboration across all platforms, and maximising domestic creative talent. “The aim is to co-develop innovative, original ideas and leverage Endemol Shine Group to take these big shows to the world stage,” he says. The outreach includes Endemol Shine involvement in re-working CCTV’s 2018 pride and joy –the mixed-genre doc/entertainment studio show The Nation’s Greatest Treasures – for the international market.

In dangling the possibility of global opportunity and programming credibility, international media groups are not only servicing their C-suite/investor hunger for a story with high-growth potential. As importantly, they are leveraging a burning desire by Chinese companies – led by state-backed behemoths – for a stronger international presence abroad.

The strategy’s latest incarnation is the two-year-old Beijing-based China Global Television Network (CGTN), launched by the all-powerful China Central Television (CCTV) in December 2016. CGTN operates six TV channels and multiple online platforms, with production centres around the world, a presence in 170 countries, a lively community on local and foreign social media platforms, a commitment to environmental issues, and the budget to acquire, for instance, global premiere rights (excluding the U.K.) to Raw documentary Drowning in Plastic from U.K.-based indie distributor all3media. The 90-minute programme, aired on BBC One in 2018, will air in April as part of CGTN’s Big Story strand.

China’s formats ambitions internationally are more complicated, with what seems like a barter approach to market access, as in “you take mine and I’ll take yours”. This all plays out against a landscape haunted by the ghosts of deals that died (or maybe they’re still alive, but the people in charge have moved on and those that remain don’t want to talk about them). For better or worse, what we don’t expect to see again is the public airing of arguments such as the one during Mip TV last year between Korea’s CJ ENM, backed by Frapa, and Chinese streaming platform iQiyi (a massive buyer of foreign rights) over Produce 101 (CJ ENM)/Idol 101 (iQiyi).

What definitely isn’t happening is any easing of the restricted access for linear television services from outside China. On the other hand, channels say, in the absence of the kind of access they once hoped for but never got, they’re doing okay on revenue from hotels and foreign compounds. Glass half-full? After more than two decades of trying, anything else has to be wasted effort.

Published in April 2019 in ContentAsia print+online magazine for MIP TV 2019